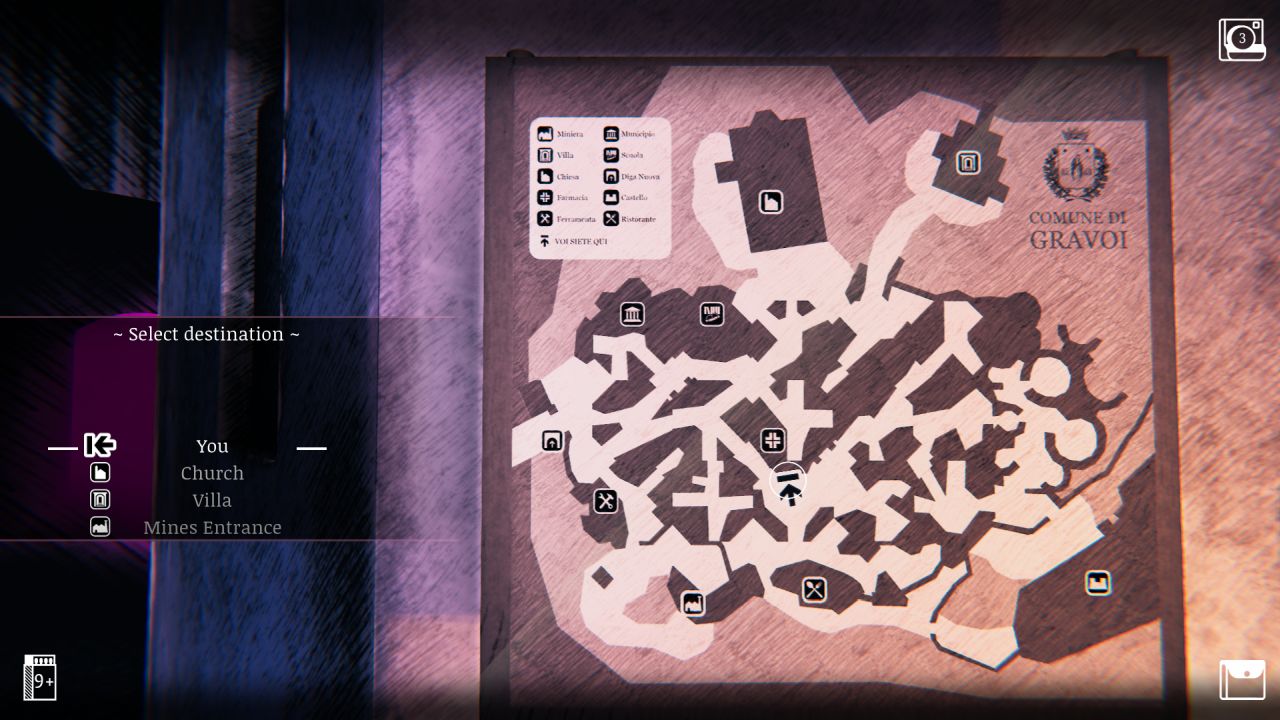

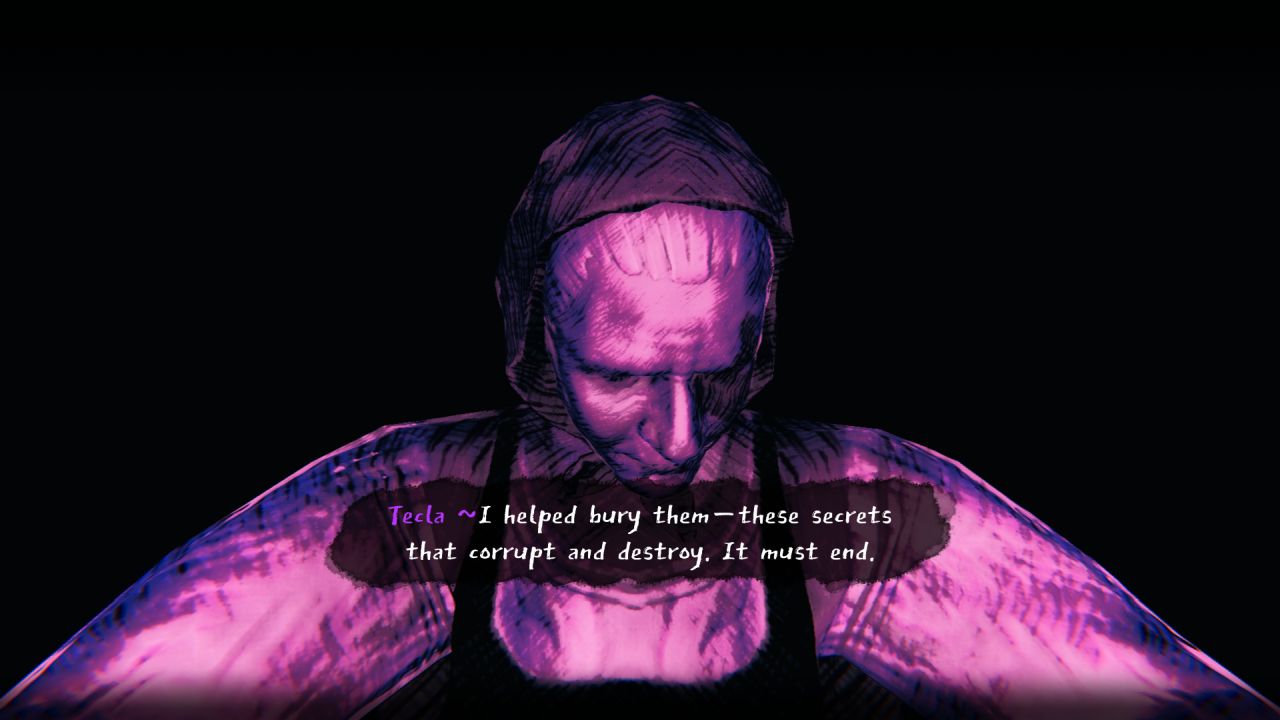

In fact it was not stillness, but the panic-sprint into darkness that became my main and oft-unsuccessful tactic whenever I heard the creature of Gravoi. Gravoi itself is a small but inconveniently maze-like fictional Sardinian town, host to a yearly folk festival that, every so often, involves the unwary being carried off and killed by a… something. Unfortunately, four very unwary outsiders - rendered outsiders for a variety of reasons, whether they’re locals or not - find themselves having to survive the night of this festival, armed with things like matches, firecrackers and a polaroid camera. You control each of the four in a collaborative effort to get the hell out of dodge, and can choose to travel alone or in a small group - but more people make more noise to alert the aforementioned rattling creature. I mostly elected to go solo, because I am a ratfuck coward. Your little Scooby Gang have different abilities: Anita has a map of the mines, and can memorise the route to any location in Gravoi that you’ve found; Paul has a flash camera; Claudia can squeeze through small gaps; Sergio has a satellite phone to call for help almost anywhere (a real coup in 1989). Each, too, has their own personal goal that it would be nice to achieve before they leave. Anita is having an affair with a local, and would like horrible revenge? to square that triangle. Paul was adopted out of town as a child and wants to find out about his birth parents. Ticking off the things on everyone’s to do list and escaping Gravoi could take you, ooh, maybe six hours, depending on your own tendency towards ratfuck cowardice, and you could elect to leave some things unresolved. That’s six hours actually in game, of course, and does not take into account time spent e.g. noping back to desktop to listen to sad acoustic songs about girls not wanting to kiss you and covers of Iris by The Goo Goo Dolls to calm down. Every time you leave a safe area to step into Gravoi, you’re vulnerable to the strange masked, creeping creature, heralded by a horrible shivering rattle - somewhere between bells and a Rainstick - that comes closer and closer until you see its silhouette. This is where I would lose the run of myself and, rather than distracting the creature by shoving some firecrackers in a bin, or finding somewhere to hide, would careen off in a random direction and get lost. Every foray into Gravoi became an exercise in psyching myself up, and a weighing of cost vs. benefit. I do quite want to check the infirmary in the mine, but also I really do not want to go back into the mine. I became intensely paranoid, convinced that I should light as few little bonfires around town as possible in case the thing could see me better, and crept around in the darkness at a walking pace. The music and sound design is excellent, and every time I heard a door slam or something crackle in the undergrowth or a weird hum kicked in on the soundtrack I got a little more on edge. There are even ways, without spoiling anything, that the creature becomes somehow even more upsetting the longer you play. And the worst part is that sometimes you’re there, all keyed up adrenalinised, and the bastard won’t show up! The nerve! Quite often, because I would panic, I got backed into a dead end and was caught. When that happens you take control of one of the other characters, and have a chance to free your pal. But if all four of the team get got then, though you keep your progress with the story, the layout of Gravoi is shuffled. Saturnalia has a literal monster, but the metaphorical one is the town. Saturnalia is absolutely beautiful to look at. Gravoi is a collection of blocky, Brutalist-ish (the most frightening yet sexiest of all architectural styles) houses in deep shadow, punctuated by bright neons that flare up in the night, sometimes clashing with the pink mist that blooms and recedes like a tide, or a heartbeat. Everyone and thing in Gravoi looks like it was drawn in pencil, so that you wouldn’t be surprised if the creature ran past with Morten Harket over its shoulder, and it’s a perfect base to receive sudden washes of colour. The design takes inspiration from theatre sets and giallo horror movies, but isn’t trying to actually be either of them - which means Saturnalia ends up feeling more cinematic and theatrical than games that try much harder to do so. There’s no menu or HUD map, so you have to use in-game map boards scattered through the town to find things. After a while you get to know where your cardinal locations are - the church, the bright blue lights of the pharmacy, the horrible altar, the yellow windows of the town hall. It is genuinely disorientating when the town changes, and you no longer have any sense of which is exactly the wrong way to run. And yet sometimes I contemplated deliberately sacrificing my remaining characters, because Anita had been taken and she had a map of the mines… Gravoi is a small town, but complex. Some locations aren’t shown on the map boards, but are nevertheless important to remember, and are cleverly marked with, say, a specific bit of graffiti or recogniseable sound. You need to find tools to open up some areas, mini-puzzles in themselves. You can collect coins to use in vending machines, or you could throw them in a wishing well, or put your hand in the Mouth Of Truth carving you can find on a wall - a notably unsettling thing in a game full of unsettling things. For the brave, the extensive mine network running under the whole town can be used as a shortcut to a few different areas. It uses the mines too I was not very brave. Like most small towns, Gravoi has a complex kind of social hierarchy, and as you play you also uncover how you’re supposed to behave if you live in Gravoi. You build up a complex web of interlocking clues and events by finding letters, old photographs, or diaries kicked under beds, and can select nexus points in a menu to see which things link together. Eventually you see how the town is so hostile to outside influence, to change, to deviation from what is considered normal, that they’ve really taken ‘better the devil you know’ to an extreme. The writing succeeds in making it all strangely poignant; you get the sense that many locals are trapped. It’s not a nice place to visit, and you wouldn’t want to live there either. Saturnalia though? That’s an experience you want to have. More and more I find myself skulking around the edges of the bell curve, looking for unusual things that provoke unusual feelings. Saturnalia is one. It’s a pulse-raising, shiver-making, dark little whisper; a beautiful game. Sometimes tiny things go a little wrong in Saturnalia - dialogue triggering at slightly the wrong moment - but you’ll hardly notice. It’s a rare game that unsettles you enough to stop playing, but attracts you enough that you turn it back on almost immediately. A rare game that’s so unapologetically specific, that doesn’t seem to have diluted any part of itself. Rarest of all is a game that’s truly unique, and makes you think “I haven’t played anything like this before.”