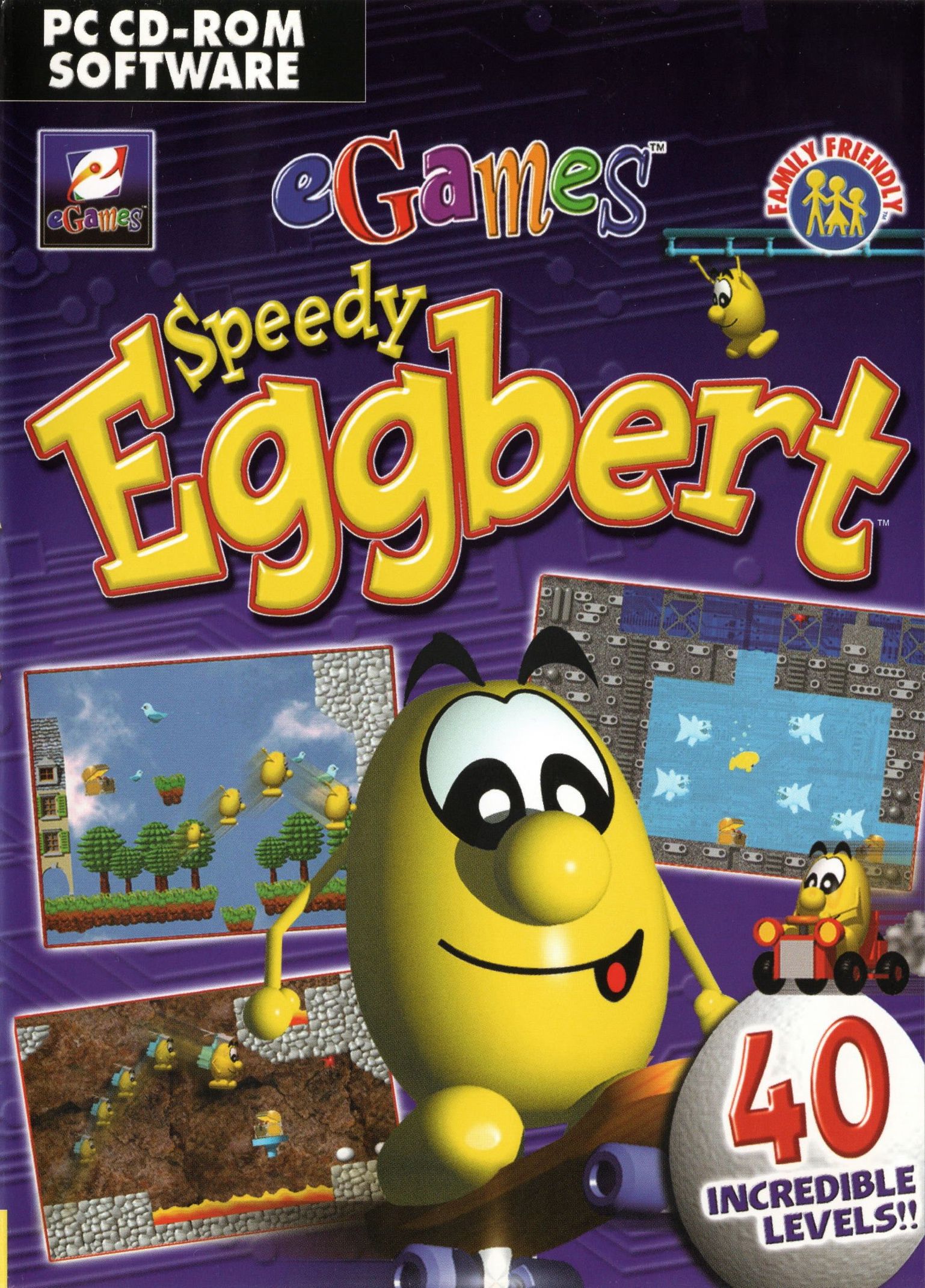

Enter Speedy Eggbert, a budget-priced platform game that scored “the world’s first generous 4% review” in PC Gamer magazine. But I wasn’t aware of that yet. I was, though, aware of its big, shiny box on the shelves of Game, with its gorgeously embossed Eggbert and a reverse emblazoned with screenshots and features, including the most enticing few words I’d ever seen – “MAKE YOUR OWN LEVELS!” Now, this was a boast to be regarded with suspicion – just because the tools were present didn’t mean I’d have the wherewithal to use them – but this was a two-dimensional platform game, my stock-in-trade; I’d been designing them for long enough on paper, how hard could it be? After a morning extolling the virtues of Speedy Eggbert to my mother, I was privileged enough to be “bought it”, and after an excruciating morning of voluntary work I was able to slam that disc into the family PC and find out for myself just where I stood when it came to this level creation business. Imagine my sheer joy, then, when it turned out to be an unbelievably self-explanatory, WYSIWYG editor with nothing to catch me out. In fact, this thing was so easy to use that it could be comfortably picked up within minutes of seeing it – my immediate peers were testament to that. Things got even better when it turned out the game didn’t even need the disc after installing; it was duly whipped around my friends’ computers and we were soon hard at work on many of our own levels. The package included a rather lengthy single-player game, but what did we care? What could we possibly have cared when the holy grail was finally upon us? Almost anything we could imagine was finally possible to make and play, and where it wasn’t we’d just find a way to represent it, or discover some exploit to make it possible. For example, the base editor came with that 2D platformer staple “secret walls”, the fake wall that you can simply walk through to find secrets. We found, though, that these passages were too obvious to the naked eye. Anyone even slightly familiar with Speedy Eggbert could identify them instantly. This presented a problem until we noticed that there was an interesting wrinkle with the game’s moving platforms. Any surface assigned to this role would no longer be a solid object, but was instead traversable from below and, indeed, both sides. Using this, you could create walls, assign them the properties of a moving platform then – crucially – not make them move, resulting in a wall imperceptible from any other, yet able to be passed through. This was like solving the Rosetta Stone, as I’m sure you can understand. It was through this experimentation that we discovered other exploits which enhanced our ability to design levels. There was a bug that made items and objects act like moving platforms, allow certain inanimate objects to become, well, animate. Elements could be combined to create new, unintended types of obstacle – for example, there was a lollipop power-up that makes Eggbert run faster and jump higher. You could use wind to create, essentially, one-way corridors. The speed boost afforded by the lollipop, however, let the player push through them, allowing for what are near-as-damnit timed entrances. You’ve got to make do with what you’ve got! Levels were easy to share, too, saved to the “User” folder on the C drive, ready to pop on a floppy disk and whip over to a friend’s house. An infinitely expandable game that constantly rewarded our creativity and never, ever faltered. Eggbert himself was a cute little fellow, too, which immediately set our overactive imaginations into hyperdrive, coming up with a whole Eggbert cast and innumerable fake sequels and adventures. My first website (Geocities, natch) was all about Speedy Eggbert, too – no levels for download, I had no idea how to do that, but tons of fan art and written content (and a single album review of Nirvana’s “In Utero”, for some reason). It wasn’t until much later that I discovered what the deal with Speedy Eggbert actually was. He was the mascot character starring in one of a series of games designed by Daniel Roux, the creator of Eggbert, and it turns out he wasn’t even called Eggbert. No, his true name was Blupi – he was simply renamed Eggbert by defunct shovelware publisher eGames, who put the game out on CD (along with a bunch of spyware) in the west, while the games were originally published by Epsitec. This expanded Eggbert’s – excuse me, Blupi’s - world even more. Me and my friends discovered the existence of the games Planet Blupi (RTS), Blupimania (puzzle game), Blupi At Home (edutainment) and, most excitingly, Speedy Blupi 2, a near-identical follow-up that offered basically the same ignored single-player campaign, but included a level editor with around 50% more elements to play with, all of which were similarly easy to use and exploitable. Keys! Doors! Circular saws! Wasps! Slime! Everything I could ever have wished for and much, much more! Speedy Blupi 2 was the most important game of my youth. Delightfully, all of the Blupi games are currently freely available, legally, from the resurrected blupi.org, hosted as ISO files. I’d recommend Speedy Blupi and its sequel to anyone with kids even vaguely interested in level design – it couldn’t be simpler to get started and (touch wood) I had no issue getting the game running on Windows 11. It goes to show that the games which inspire creativity and community are the ones that mean the most to you. Even if they did only score 4% in PC Gamer.