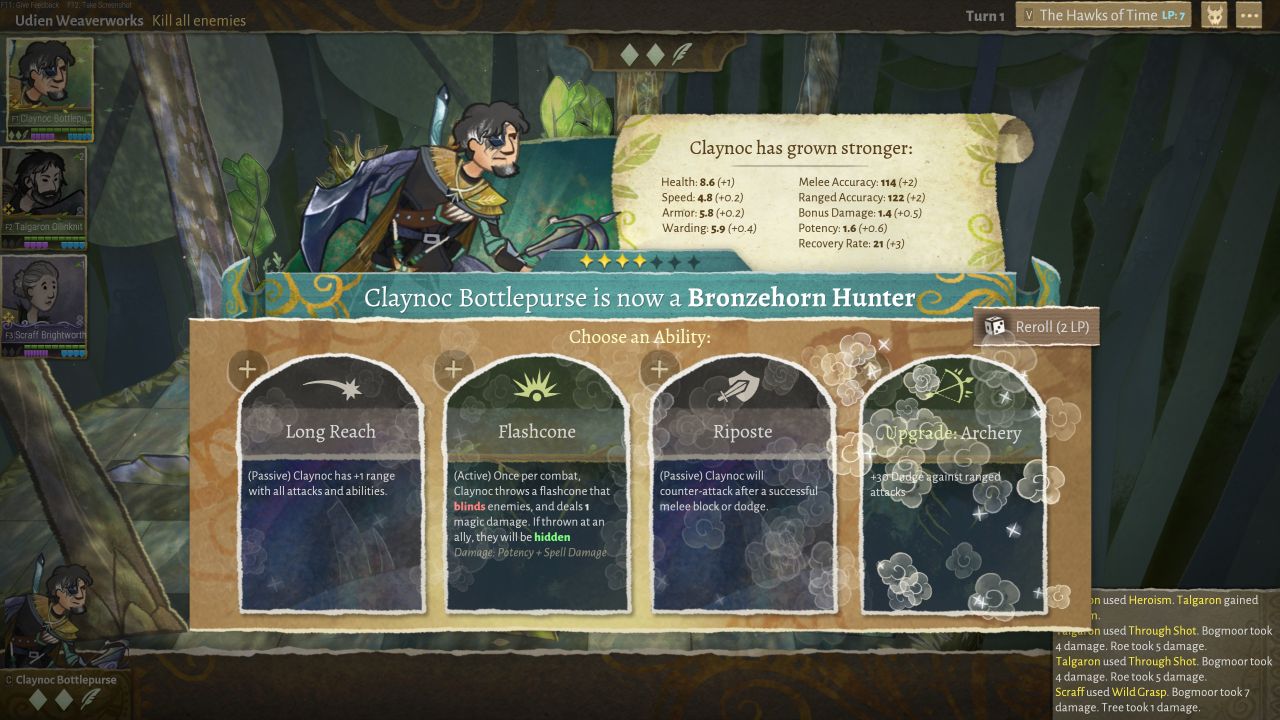

Wildermyth is an inspired example of narrative design, with some nifty tactical combat to boot. But when Nate Austin, his wife Annie, and his brother Doug began developing the game around eight years ago, the weight of emphasis between storytelling and combat was very much the other way around. “All three of us had been playing X-COM a lot,” says Nate, who co-owns Worldwalker Games with Annie, and is the primary programmer on the project. “And we love the stories that are generated. But we wanted a lot more detail about the soldiers.” Nate was working for Riot Games at the time, while Annie at Heavy Iron and then at Gamesalad, and Doug was finishing college. But the three got together at thanksgiving one year and sketched out the rough idea of what would become Wildermyth. “Part of the inspiration was to just to take some of those ideas, and some improvements that we wanted to make, and put it into a fantasy setting, because we felt like that would fit better.” One of those improvements was to character progression, for which Nate was inspired by his work on League Of Legends. “One of the things that I really love about League Of Legends is the champ roster, and how different all of the League of Legends champs look and feel and play,” he says. “That’s something I really wanted to bring into our game, where it was about telling origin stories for all these crazy heroes where they start off as farmers but like somewhere along the line something happens… and they’re transformed in these really visual ways.” The original pitch for Wildermyth was a turn-based tactics game with League-style heroes at the centre, who evolved into those heroes as a consequence of your actions during battles. For example, characters who fell in battle could end up with permanent injuries like missing limbs, and then go on quests to have those injuries healed, or their bodies augmented into something greater. But two things happened that began to shift the emphasis of Wildermyth. Firstly, the Austins realised that tying story events to character deaths and injuries had some unintended side effects. “We were incentivising all our players to kill their guys because they wanted that wolf-arm or whatever,” Annie points out. Second, the stories being written by Doug Austin, the game’s lead writer, were far too elaborate to act as mere filler between missions. “A big thing that I wanted out of a game, if I was going to work on it, was to find a way to take those emergent details and like, bring them into light and flesh them out a without forcing all that effort on the player,” he says. Doug had a particular vision for the kind of stories he wanted Wildermyth to tell. But there were some practical hurdles to him achieving this. At this point, Wildermyth was very much a side project for Nate and Annie, with no real budget or rigorous development plan to speak of. Doug, meanwhile was fresh out of college and figuring out what he wanted to do with his life. “There wasn’t a job to give me,” he says. “So I was just like, ‘what’s my actual career going to be?’” Doug left the project and wouldn’t return to Wildermyth for another two years. But those limitations on both budget and time did help define other areas of the game, like its papercraft art-style. “We knew we were going to do 2D because I’m not a 3D artist at all,” says Annie, who creates all Wildermyth’s art. “We specifically went real minimal on animations so that we can have all these rigs [static character poses] where the hunters are holding a bow and the warriors are holding a spear. We can’t animate a bow drawing with that. And they’re all gonna have different outfits.” Given the sheer number of character permutations Wildermyth has, the decision to go without detailed animations made the art workload more manageable. But it also raised a question over how the developers would represent the game’s tactical combat. Since the game was already heavily influenced by papercraft, it made sense to take further inspiration from the physical world. “What do you do when you’re a little guy in a boardgame and attack?” Annie says, before miming using one boardgame piece to knock down another. Annie states that it took a couple of years to properly pin down Wildermyth’s visual style, but it had the advantage of being consistently worked on by one person. The writing, however, was much harder to define. “We hired some contract writers, and soon we realised that what we wanted was actually pretty unique, and that we weren’t doing a good job of explaining it to the writers,” Nate says. “We had to go on a big journey to learn about what that actually was.” A crucial stepping-stone in that journey was Doug’s return to the project. “I wanted to bring a certain lyricism into fantasy writing,” he says. “And some magical realism to the fantasy genre, where the characters feel very real and very normal.” Doug also wanted the characters to have “a casual tone” around the stranger elements of their world. “[If] this is the world I live in, I’m not surprised by the fact that there’s magic around me, because it’s always been around me.” Tone was also tricky to pin down. The Austins knew they didn’t want to go grimdark like Game Of Thrones, but they also didn’t want the game to be too light and quippy and insincere. “We wanted to treat the world with reverence,” Doug says. “Not undermining the seriousness of all the life and magic and beauty that we’re implying.” The more seriously the Austins took the storytelling side of the game, the more Wildermyth began to come together. For starters, thinking about story and character helped give the tactical side of the game more shape. “One of the major [design principles] was to make you think a lot about teamwork,” Nate says. “To have where everybody is standing be important and what everybody’s actions are important, so that you wouldn’t just have one hero carrying the fight. You really need teamwork, and a lot of that is about positioning.” They also found a way to make all the random stories that players encountered on their journey feel like they mattered. “We had, for a long time, this concept that everything would be procedural and every story would be dynamic. And at one point in 2019, we were like ‘Alright, let’s try and make a cohesive villain from front to back. That’s how the first Gorgon villain came about,” Doug says. “The random events started to make sense a lot more because they took place within this plot structure.” By this point, Wildermyth had a compelling blend of procedural storytelling within more hand-crafted arcs, and a solid tactical combat system with a winning papercraft visual style. But connecting the two together was a problem they still hadn’t solved, and arguably never did. The system they came up with was an overland map, a kind-of meta-boardgame where the player’s party moves between different regions of Wildermyth’s world to scout them, doing which triggers a narrative event. It works well enough, but Nate believes it could be better. “The original stuff was much more simulationist. Instead of having tiles, we had an open map with features on it in different places,” Nate says. This map had systems like populations that grew and shrank, and dynamic threats made travelling more risky. But all those systems made it difficult for players to understand where to go and what to do. “We threw away a bunch of work on that in order to get to something that was simple enough and worked well enough. It’s still not the part of the game that anybody gets excited about,” he adds. By the time of the game’s Early Access launch in 2019, the Austins felt like they’d made something fun and interesting. But they didn’t have a read on how other people would react to it. “We were taking it around to conventions for a while,” Nate says. “And the thing about it that the magic of the game is in caring about the characters, [which doesn’t] really hit until you’re like three or four hours in. So if you’re going to a convention in Florida, you’re like ‘Ok, I played a mission for ten minutes and that was fine, nice combat I guess’ and then you walk away.” Nate says that, prior to launch, they were “hopeful” that they’d recoup the money they’d spent on paying contractors. But when the game launched into early access, it far surpassed their expectations. “We were very pleased and happy and surprised by the response. It was awesome.” Since that early access launch, Wildermyth has gone from strength to strength. It saw its official 1.0 release in July last year, launching with five bespoke campaigns to rapturous reviews. The last twelve months have been mainly about post-release support, which will continue for the foreseeable future. “We can just keep cramming stuff in,” Doug jokes. “The stories are so modular it’s just like ‘I wrote a new one, put it in’”. Wildermyth may have started out life as a fantasy X-COM with richer characters, but it ultimately became something much more novel and distinctive, one of the most innovative narrative RPGs of recent years. This happened, the Austins believe, because they asked at every step of the project whether new ideas and features were actually interesting, and served the vision for the game. “Make every decision. Don’t have hit points because games have hit points,” Nate concludes. “Decisions like that, we try to make them very intentionally, and hopefully you end up with something that doesn’t feel like it’s a copy.” Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that Annie Austin had also worked at Riot Games. This has been corrected.