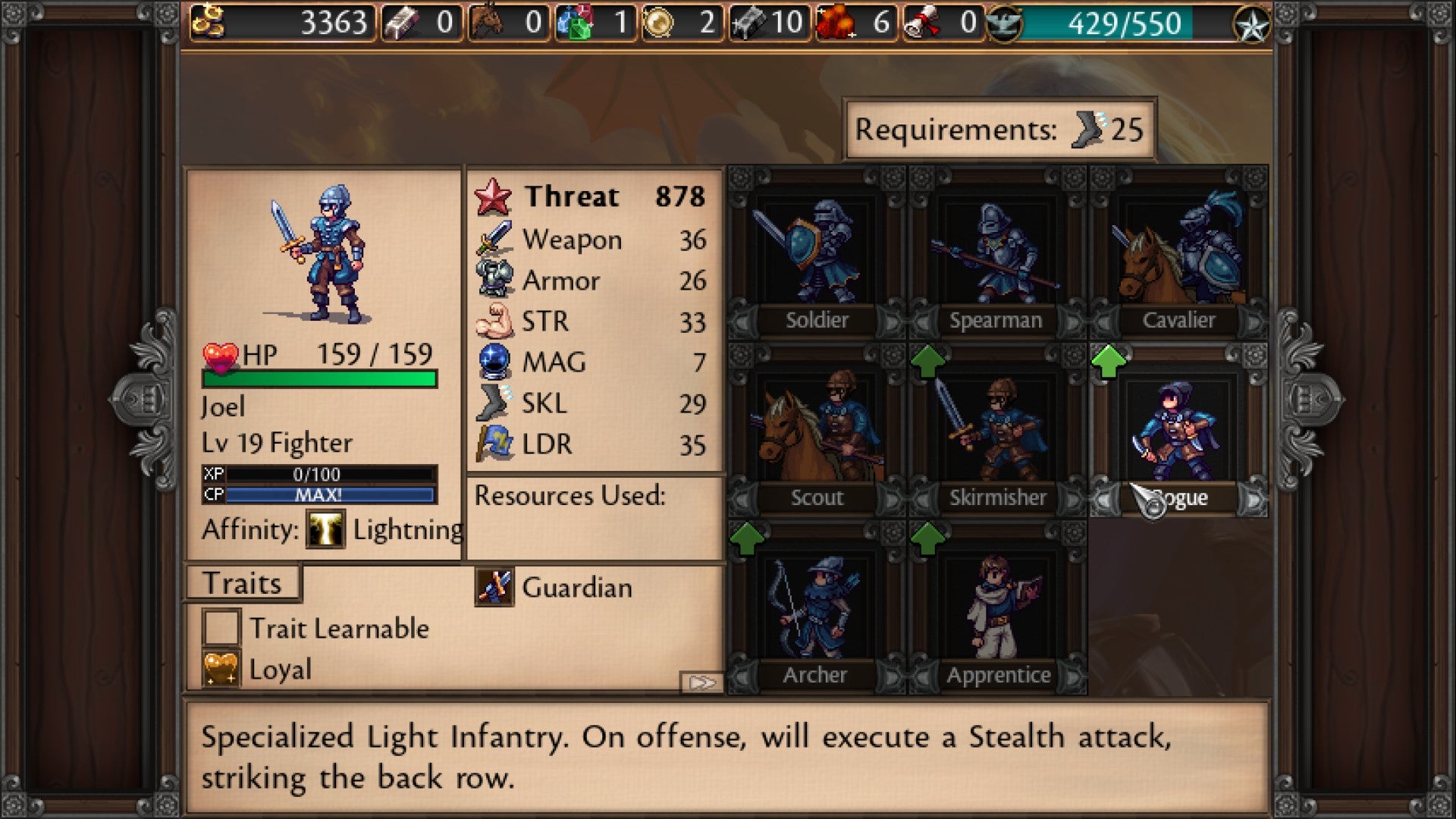

That’s a pretty big statement, and I’m as surprised as anyone. Going in, and even after a few hours, I’d expected to come out of this writing something like “great game hamstrung by its engine”. I’ve played some great RPG Maker games, and some of them weren’t even fetish games, but it does lead a great many of its users down the same awful design paths. Symphony Of War sidesteps or heavily mitigates most of those common flaws, leaving its biggest issue a cumbersome user interface. That I say “cumbersome” and not “fatally terrible” is a credit to the work Dancing Dragon Games put into beating the z-list JRPG framework into a top drawer strategy/tactical RPG that compares perhaps most recognisably to Advance Wars. Or Ogre Battle 64, but come on, you’d never heard of that before this week either. You lead an army through a linear campaign of turn-based battles where the goal is generally to capture an enemy stronghold or deliver a specific squad to a given square. I say “squad” because although the details I’ll elaborate on later enhance the design a lot, the fundamental element that marks it out is the way your forces are organised. You’re not leading discrete single-soldier units around, nor platoons of uniform stabmen a lá Advance Wars or, say, Master Of Magic. Instead, you recruit dozens of named individuals, assign them to a “squad”, and then command that squad as a singular unit. Sure, your squad could just be five archers, or three spearmen. But it could also be a lancer, an assassin, two priestesses, a rifleman, and a sorceress. The next squad along could have an entirely different setup, especially since the limits of how much a squad can actually fit in depends on who’s leading it, and any but the most entry level recruits can be a squad leader. Each has a class, and can graduate to a wide variety of better ones (or even be downgraded if for some reason the new job’s not working out). But each recruit is unique; not only does every individual soldier or healer or infantryman start with different statistics, but they gain them at different rates too. Squad assignments are impermanent, so you can freely move anyone from squad to squad in between levels, or disband your entire army and reorganise it again from scratch (with the minor exception that key plot characters must all lead a squad of their own rather than Wu-Tang it). This has huge ramifications strategically and tactically, but just as important is how recognisable it makes your army. These are your guys, your specific guys, who are leading a squad of their own because you asked them to. That attack didn’t fail because the swordfighters are bad units; it failed because you put them in a squad without a healer, or a front line to protect them from counter-attacks, or you put too many heavy units in with them so they couldn’t ambush properly. Or perhaps you’re thinking small, and you should pair Tilda’s whole squad in with Noel’s valkyrie/ranger team. These decisions and relationships aren’t static either, because recruits grow into different niches. By the second third of the game you’ll be looking forward not just to the battles, but to the bits in between. There you get to recruit entry level units, plus a limited few more specialised ones, and buy some artifacts to attach to squads for various boosts to differentiate them further. Other items can permanently boost individual recruit’s stats, or inject them with a trait that makes them steal money from enemies, get a free bonus attack at the end of a fight, do extra morale damage, or heaps of other possibilities. All this adds even more to the adjacent part, where you’re moving units in and out of a squad to see what you can do with your dudes. Perhaps you have a lowly archer who’s become a capable leader of his own squad thanks to capturing so many surrendered enemies. An acolyte from Diana’s front line might graduate to a paladin, whose excess power isn’t necessary for her old group but would protect Ingraham’s rangers from cavalry charges. I even found myself demoting one leader of a pure spearmen squad who kept getting wiped out despite several defensive advantages. One of the others had simply become a better leader, allowing me to put him in charge and add a healer to the squad, giving them a much needed resilience boost. To help him find himself, I gave the demotee the ‘bodyguard’ perk so he’d fight tooth and nail to protect his own replacement. What a champ. Adding even more to all this is a tech tree that encourages specialisation in a branch (or rather, to prioritise one, and neglect one branch of three until later in the campaign). Right from the off, you can afford more troops than you can field, so you’re thinking of what form your army will take long term instead of having it dictated by circumstance. I wanted an army of light guerrillas and spearmen backed by healers, so that’s what I hired. The “mixed unit tactics” research grants a cumulative bonus to haphazard squads, enhancing my natural tendency to embrace chaos, hence the irregular arrangements you might have noticed in screenshots. There’s an order to it, but instead of uniform units, each team is part of a larger strategy. But your army could be all clean and efficient, and that’s fine, because it’s your army. The tech tree emphasises this further, with real differences between an army that focuses on resources and quality equipment, and one that focuses on broadening tactical options, and a third that prioritises raw unit skill through training and specialisation. You’d assume the newfangled firearms would totally outmode archers, but they’re slow and cumbersome, and my favoured strategy of ambush and assassination (reducing morale, which weakens enemies and makes them more likely to surrender, which in turn gives you ransom money) really wears them down, and my focus on light units reduces the advantage of their armour penetration. You really feel like you’re making the decisions, but not the trivial ones. Crucially, once a squad attacks another, all you do is watch. There’s none of the tedium of repeatedly telling a soldier to twat the guy in the face. Instead, you get to enjoy the excellent and satisfying animations and sounds as your soldiers all leap at the enemy, cavalry charge over, and apprentice mages casually detonate enemies almost over their shoulder, while reading a book in the other hand. It’s here where you come to love specific characters for their habit of getting a free shot in at the end and finishing off a troublesome mage, or for beating the odds to weather a brutal artillery barrage three times in a row. I want to recommend the “permadeath” option because Symphony is a little on the easy side for an experienced strategy player without (and you’re refunded any resources spent on upgrading a character if they die), but god, I don’t know if I could take the heartache. That’s another interesting effect of the whole squad system; a bit like Freedom Force Vs The Third Reich, it helps to develop a capable bench. Sure, it’s tempting to have one or two super strong squads do all the work, but beyond a certain point, excessive force is precisely that, and you’re better off using those squads as trainers, promoting overlevelled fighters out to where they’re needed more. The campaign does a good job of varying your objectives, and often has you split your forces across multiple starting areas to reflect a battlefield situation. Sometimes you’ll be two-pronging (pronggg) an assault through a marsh and grasslands, sometimes rushing to lift a siege for a potential ally, sometimes cutting a fighting retreat. There’s a section in the middle where you temporarily trim down your army to its core, and I found myself choosing not the most effective or balanced squads, but the ones I plain liked the most. In theory the ideal force would also take into account each recruit’s “element”. Each fighter (not class) has one of your classic water-air-eggs-trees-etc. deal that determines which statistics they’ll raise quickly or slowly, and also which other elements it will counter or struggle against. But this is where the interface really chafes (and where the game would be excruciating were it keyboard-only. For the love of god, use a mouse). There’s a clear and useful encyclopedia menu, but it takes a lot of clicking back and forth between both it and each unit, and the element guide specifically is so unclear that I pretty much ignored the entire system, and only for this sentence remembered that weather and time of day are factors too. But I was able to ignore it and still feel informed and empowered to organise and fight how I wanted to, largely because I felt so responsible for my plucky randomly-generated wardudes. Frankly, I became more fond of these walk-ons than of the main cast, who are… well, they’re fine. I won’t pretend I didn’t skip the cutscenes for a mission or two, but I came around quickly. A menu option at base lets you review non-critical conversations between characters that develop their relationships, and even add little asides to the epilogue, Fallout-style. It’s a cute detail but the writing doesn’t really do it justice. The story otherwise is basically fine, but I liked the opening acts more for being about political ambition and civil war. It soon devolves into your usual The Evil One Cometh vs The Prophecy Ladder fare, but it’s alright. On the grand scale the beats are fairly obvious and I literally called out one character as a traitor instantly and had to wait hours for my character to catch up, but it’s alright. I do wish it stayed about power hungry politicians rather than Let’s Awaken The Dark Lord Oh No My Soul How Could This Happen again, but, y’know, it’s a fantasy game. It had dragons from day one, so it’s not like I wasn’t warned. More importantly, the game’s structure remains varied, breaking you out of complacency and switching up the perspectives you play from, without ever overwhelming the player or capsizing the boat. I could go on even longer about how all these simple systems interact, and little details emerge the longer you play. The moments of drama and specific characters who did something I enjoyed. Symphony of War is teeming with the exact kind of thing you likely want from a tactical RPG and I can’t possibly hold its few flaws against it. Go and assemble your own wee warchestra.