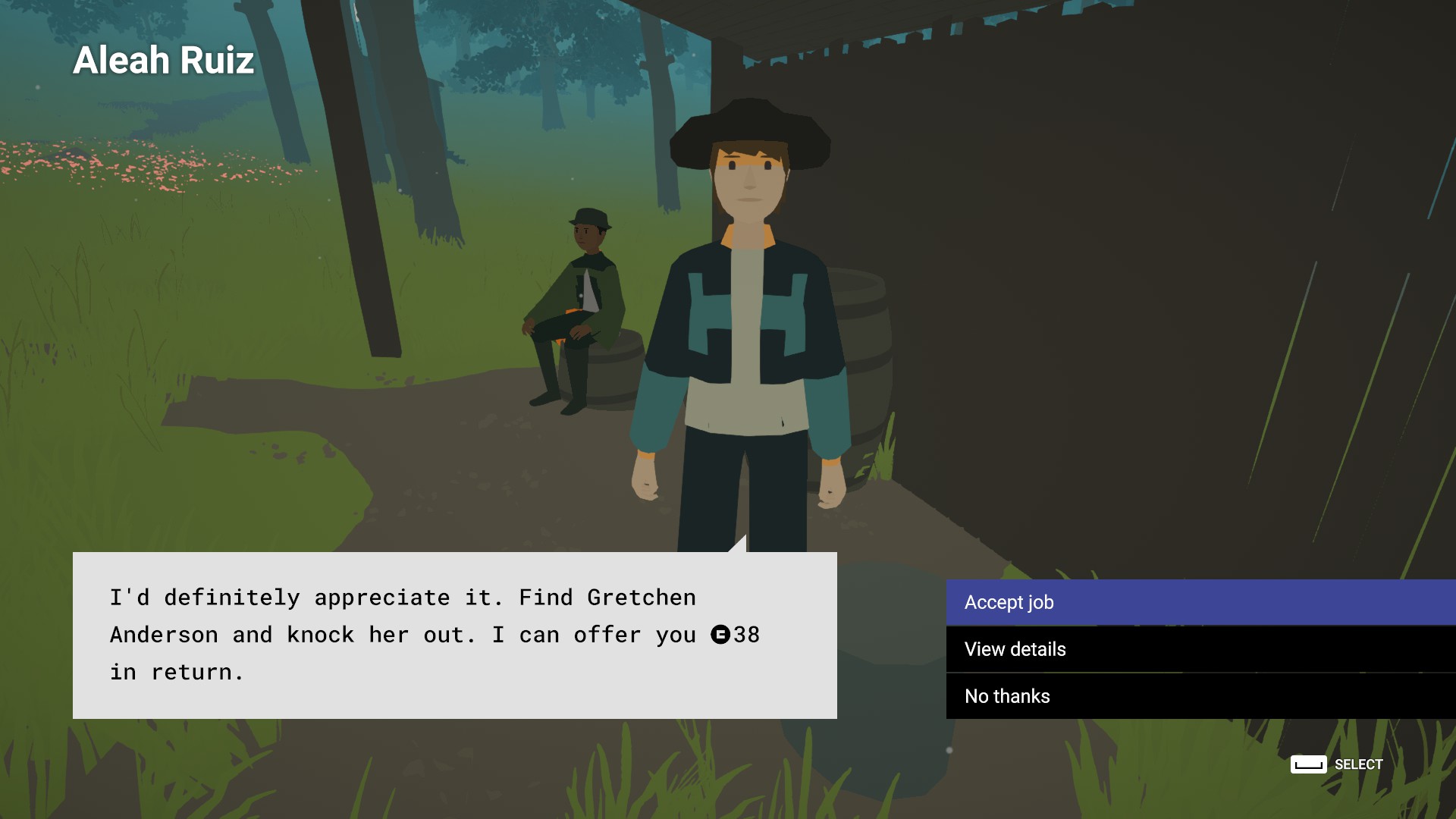

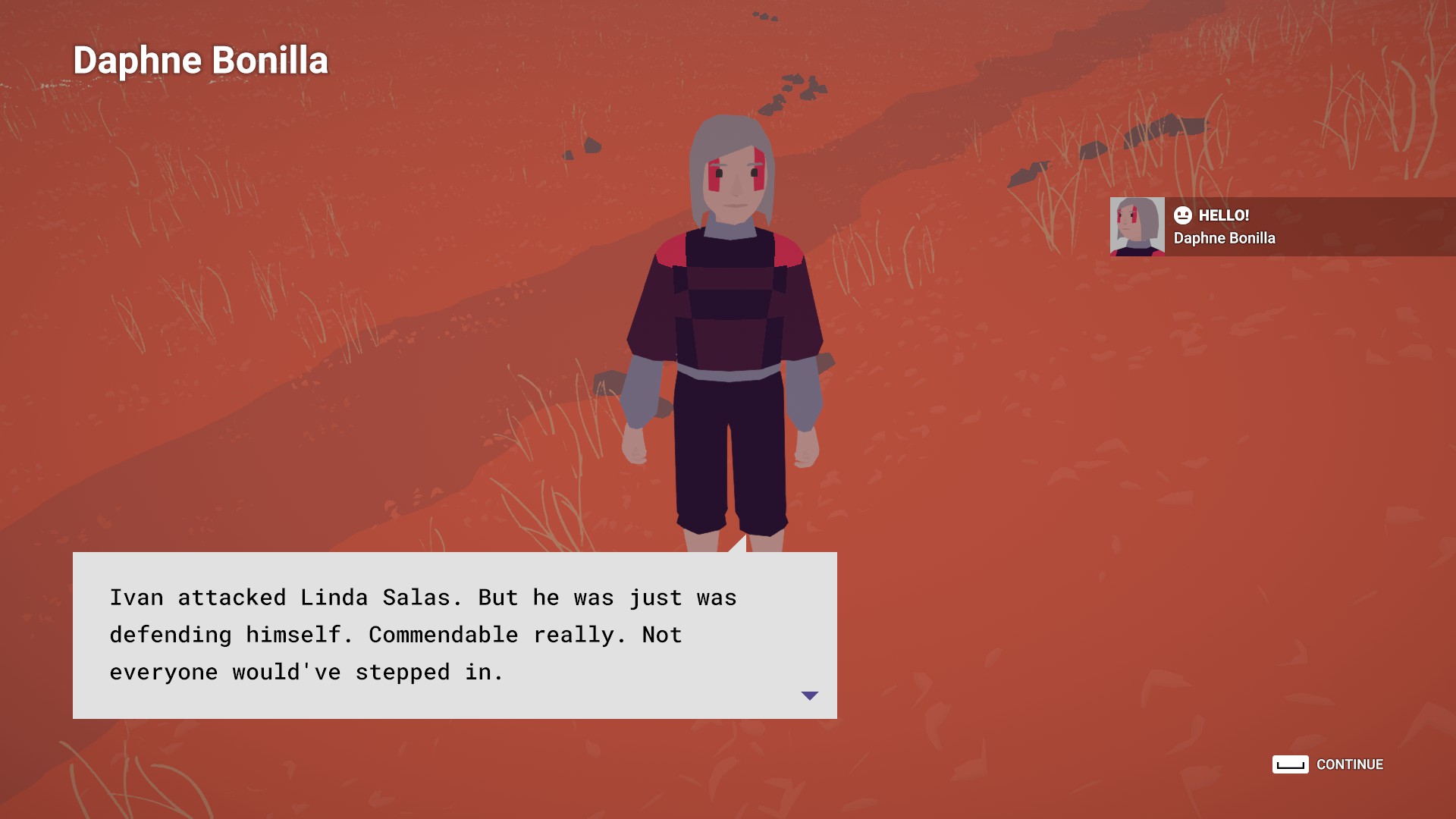

Thousand Threads is a walking simulator with an open world light RPG-ish simulation on top. It is a little bit, like Death Stranding, about how a courier or postman can hold a society together. It’s a vastly more relaxing and low-key game, and about walking in the woods and observing the dynamic behaviour of its many NPCs than rebuilding or fighting or pontificating. There’s not even a story as such. But through playing it over these last few days, I have come to understand that it is not, in fact, the player’s role as a noble postal worker holding this society together. It is Gretchen Anderson. You can hunt deer and rabbits, sell their meat and pelts, or upgrade items with it. Each person in Thousand Threads has a name. They have a home, a mail box, and usually some relatives. They all have a personality too, and their own habits and patterns and concerns. They will often sit outside their house, or dotted about the village centres, but sometimes they wander. There are dozens of them, many of whom you’ll forget, but a few will become familiar. Your job, although honestly it’s more of a thing you just take up because why not, is to find these people, and deliver letters to them. You can also pick up and carry out odd jobs for any of these inhabitants, which is the RPG layer. These are randomly generated, although many are dynamic too, as they’re based on the relationships and actions of both you and other NPCs. Someone might ask you to carry a gift to their daughter, another person you meet on the way will ask you to gather wood to help them with home repairs. Another might tell you that their friend was attacked, tipping you off that the friend might need help when you find them. It was a while before I realised just how much attacking goes on in this place. Thousand Threads remains a wonderful place to walk around, and its people are capable of sweetness. But the dark truth is that the cornerstones of this society are soap, wildflowers, and twatting people in the face. They are a sentimental, violent, respectably clean people. Some of the jobs, you see, are based around avenging crimes like robbery and assault. Susan Rasmussen might have been ambushed while out walking, and ask you to question witnesses to find out who did it, then deliver the perpetrator a solid thumping. Others, however, will ask you to pummel someone just for being annoying. Several that I’ve caught in the act of lobbing stones at someone, smacking them down, or even looting a body, will insist that they were merely defending themselves. It’s left me paralysed with indecision whenever I come across a fight on the road. It might seem obvious to attack the aggressors, but I have no idea what this is about! They could have it coming for all I know. There are no generic “bandit” type characters like in most RPGs, hostile to everyone for the sake of convenience. It’s just village after village full of beefs and petty disputes, simmering resentments and the occasional person who’s just a plain dick. At first I turned down the violent jobs. Nobody wanted anyone killed, although you can murder almost anyone. Much like Gothic, NPCs are satisfied with knocking each other out and sometimes taking items before their victim wakes up, but to kill someone takes a deliberate attack on a helpless, unconscious person. But even so, it didn’t feel right to start attacking people. I mean, we’ve all known someone who gets on our nerves. We’ve all thought about hiring a wandering mercenary to brutally club them into unconsciousness. But we don’t actually do it. This is a small community. I even helped some up, applying restorative herbs I’d made from the many flowers I picked to anyone I found on the floor, even if they started the fight that put them there. NPCs will attack each other from time to time. I’ve seen group fights, animal attacks, and even a woman robbing someone while proclaiming aloud that she’s merely taking back what’s rightfully hers. It troubled me, and yet I like the ambiguity about it. You can take sides based largely on your own personal preference, or be like me, a sort of neutral wandering healer. At first I didn’t know the parameters of the game well enough to start combat, but then it became unwillingness. I don’t know the full story. That person could be attacking you because you beat up their son. They could be attacking because they just don’t like you. I will just help tidy up afterwards. But I kept hearing about Gretchen Anderson. I didn’t remember her name at first. I’m unfocused in gathering and completing jobs (and I turn a fair few down anyway), and there were so many names that I didn’t pay much attention to them for a while. Much of Thousand Threads is very much about taking your time, enjoying the scenery as you stroll through its multiple areas. The odd jobs were a byproduct of that, a bit of opportunism. They made me a little money, sure, but there’s little I really needed as I wandered the woods and savannah, picking flowers and later breaking down stones with my handy pickaxe. You could play like this for hours and never bother anyone. It even lets you choose whether to read the letters before delivering them, which is tempting when you get three or four addressed to the same person at once. It is a game weighted towards chilling. And it even does a thing far too few games do: there are long stretches of silence between the music, making it feel much more valuable when it starts up. I only took note of Gretchen through sheer repetition. Someone beat me up the other day, says Mary Wilcox. That’s rough. Gretchen Anderson you say? I might keep an eye out, I thought, instantly forgetting to. But then later I spoke to Nayeli Summers, whose mother was beaten up by Gretchen Anderson. Someone’s slandering poor old Brenton Graves? Who’s… oh, Gretchen Anderson. It got wilder. As you wander the world, you occasionally find a new region. There’s only the one map, and it’s not brimming with stuff the way a Skyrim or Witcher is. There are plants to pick and houses to visit, but mostly it’s a case of tracking down people to give them letters or do odd jobs. You do this by asking around, with a pretty decent menu that automatically prioritises people related to jobs or letters you’re carrying, but you can ask anyone about anyone else. Not everyone knows everyone, particularly if they’re from a different region, so you really do have to ask around, and when I started asking about Gretchen, nobody had anything good to say. “She’s the worst” was almost universal among people who knew her. Even one of her kids claimed not to have seen her recently, evidently knowing better than to grass. But beyond her family, Gretchen’s arseholery was the talk of the town. She beats people up. She steals, and denies it. She spreads slander, and taunts people to their face. She has enemies in every region I’ve visited, suggesting that she walks through deserts and baking plains for several hours purely to antagonise others. In the rustlands, two whole regions away from her home, I met someone who has a beef with her: Gretchen inherited someone’s stuff, and another friend of that someone wanted a mere lock of hair to remember them by. Gretchen refused. By this point I had met about half a dozen people willing to pay me to kick Gretchen’s face in, and it started to occur to me why I was so reluctant. If the “thousand threads” are the lines of communication that make a society, Gretchen Anderson here is a most crucial one: the local villain. There’s a bit in Malcolm In The Middle where Malcolm is upset because he’s realised the whole neighbourhood hates his family. His mother Lois shrugs it off, saying: “These people need somebody to be mad at. Having us to hate gives the whole neighbourhood something to bond over”, while his dad Had cheerily agrees: “Communities seek out a common enemy. If it wasn’t us, they’d all team up against someone else.” There’s the most perfect pause before he adds “Probably a minority.” I guess what I’m saying is, maybe Gretchen Anderson is Lois. Maybe these people need her. Without her they’d be beating and robbing each other, accusing at random, avenging on a whim. It would be chaos. She is the mortar that holds society together by keeping us apart. I have nothing but admiration for her sacrifice, for her dedication, and for the level of petty she is capable of achieving. I’ve made enemies by getting involved in other people’s business. When I saw someone being ambushed and robbed, I told them who did it, and doled out a retributive beating. I bartered for a stolen item to return it to its owner. In a second playthrough, I did a murder, and approached someone I’d secretly robbed early and offered to investigate my own crime (I made sure to do this while brandishing my hefty walking stick at potential witnesses, so they don’t get any ideas). But Gretchen Anderson is the real protagonist here. She must never be harmed. She’s too important. Thousand Threads is out now on Steam for £15.50/$20/€16.80.