This isn’t the kind of gaming anecdote that ends in comedy chaos or unexpected consequences. The railway simply worked. The very best moments in Transport Fever 2 unfold exactly as you plan them to. It’s the satisfaction of yelling into a cave and hearing a perfect echo bounce back.

Caves aren’t exactly where Transport Fever 2 begins, but it is a game that takes great pleasure in telling the story of infrastructure from its earliest days. It’s a pitch that stretches the budget somewhat, as the first campaign’s narrator gamely attempts a Nevada pioneer’s drawl, and the wagon stations emit the unmistakable pneumatic hiss of 20th century buses. But the structure is largely welcome, since the history of infrastructure turns out to be one of increasing complexity; it begins with single railroads and cart trails, and ends with one-way routes and bus lanes. Your remit is much the same as it was back in Transport Tycoon, a management game released contemporaneously with the Nevada gold rush. Essentially you’re playing in the margins of a game of Sim City, feeding towns that preexist you with roads, railways, ports and, in later years, airports. If you do it right, those towns grow before your eyes, getting fat on the bread from factories you supplied with grain. In turn you benefit from their prosperity, building their bus routes and bundling the population into trains bound for nearby settlements ripe for similar expansion.

The goal is to make that invisible Sim City player happy, so that they can make you happy in exchange. The trouble is that too much else in Transport Fever 2 is invisible, and that learning to interact with its beautifully organic simulation is a matter of bumbling in the dark. Despite its long and tutorialised campaigns, Transport Fever 2 often does a very poor job of explaining the essential systems operating under its surface. For a long time, I wasn’t clear on the way materials flowed from one building to the next - I’m sorry, Glasgow, for the many superfluous truck stops I stuffed into your crowded streets. As it transpires, goods move automatically from factory to platform so long as they’re in close proximity, by osmosis - a slow realisation that saved many thousands of pounds thereafter.

Clarity is complicated by the fact that the goods - whether that’s steel or people - won’t show until a line’s already operational. That makes troubleshooting tricky, since a mistake made at any point in a route’s construction might result is a whole load of nothing coming down the pipe, with no immediate way to locate the problem. You’re left like Tom Hanks in The Terminal, staring at the waterless fountain he’s spent weeks building, wondering where he went wrong with the plumbing. Even when you get a line up and running, you’re often operating at a loss until the materials accrue to make it a success. Which might not be obvious unless you’re looking at the line statistics screen, opened via a tiny icon in the bottom right. It’s practically Transport Fever 2’s home page, the only way to be certain what’s profitable, and I’m not sure the game ever points it out.

Once you become accustomed to the placement of all these peculiar knobs and levers, however, everything that was counterintuitive starts to make sense. Of course you can’t tell exactly how much demand there is for a new train route before you build it - that’s not how real business works. You must be the bird, tapping on the earth to bring out the worms. Sometimes they don’t emerge, and you have to accept the loss - preferably quickly, for the sake of your bank balance. On the flip side, there’s no greater high than discovering a line has taken off and clicking the button to double its fleet of vehicles. It’s an immense and quiet pleasure to slowly coax the potential from a place.

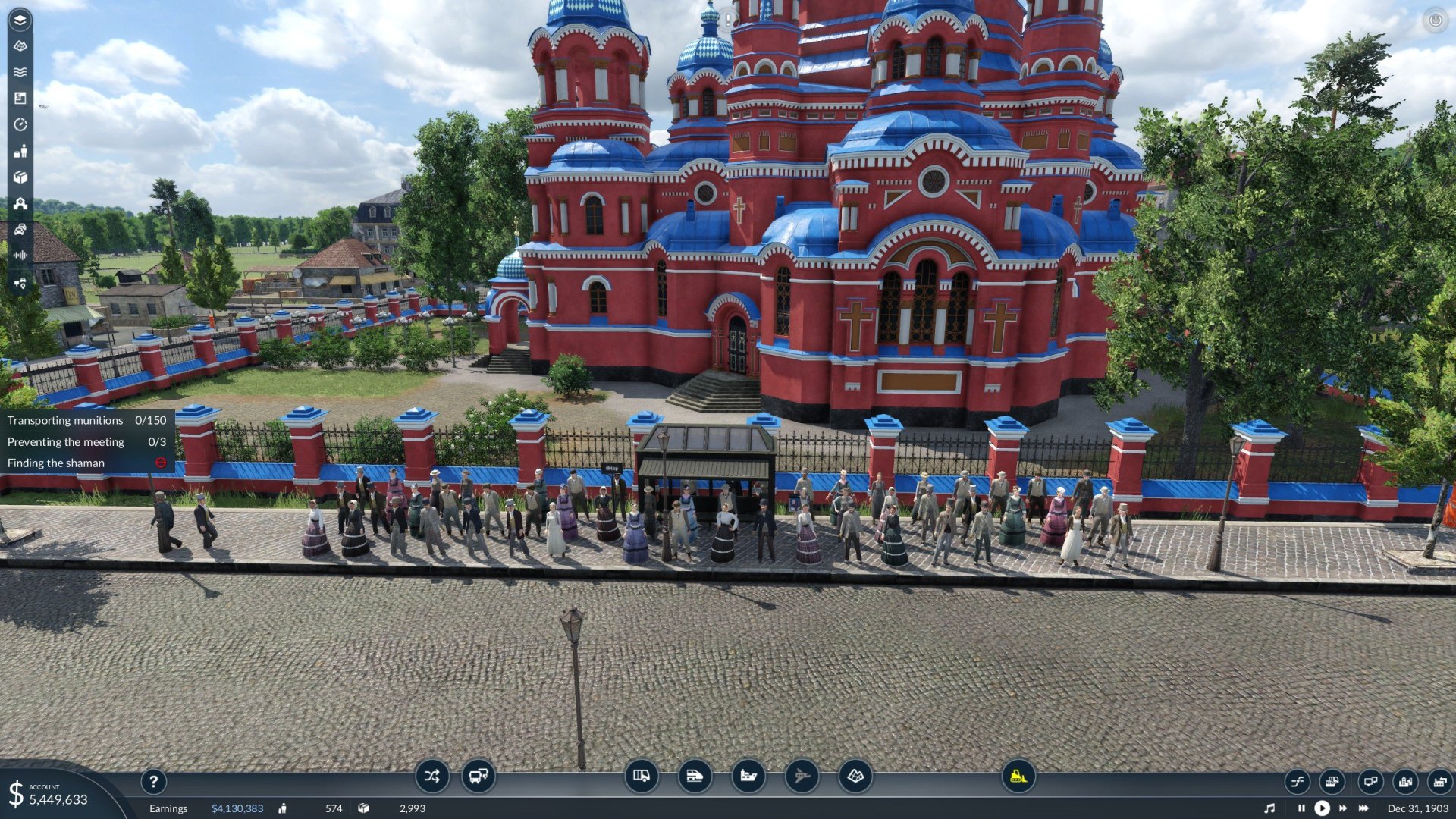

The first of three campaigns opens with a disclaimer that its scenarios deal with stories of historical suffering and oppression - often from the perspective of the oppressors. The island of Java is hailed as a fantastic source of cheap labour for coffee plantations. There’s no way to escape the political dimension of a 1904 mission to build a railway in Baghdad that ends with the command: “Quickly pump out a few more tankfuls of oil and then get out of here”. But the teachings developer Urban Games attempts to impart are, like my bus routes, only intermittently successful. These twists are delivered with gentle irony rather than real weight. Tonally, we’re closer to Tropico than Frostpunk. That tone is further confused by a series of odd side quests that have you hunting for shamans, solving daft puzzles, or in one case, literally counting sheep by clicking on them all over the map. While these diversions sometimes use the tools inventively - digging for an ancient city by terraforming, for instance - they feel as if they belong to a different game. An officially licensed Where’s Wally adaptation, perhaps.

Occasionally, Transport Fever 2’s more overt messaging hits the mark. My contributions to the Trans-Siberian Railway triggered tensions in the east, and before long I was delivering munitions to the front, down that same line I’d been so proud of back when it transported steel. But it’s a game at its best letting you write the script - laying down the lines, setting the routes, diagnosing issues, and owning the results when it comes good. Oblique though it may be, there’s an extraordinary simulation at work here - one that refuses to be gamed, and teaches you that transport is a service, rather than a money-printing exercise. In my experience, a great management game is distinguished by its central lesson, and Transport Fever 2 has one worth learning.