The music of our 1980s is rooted in our postwar reality, tied to its precedents of the 1970s - particularly punk music and punk culture - and a further evolution of postwar youth culture. But how could musical ideas like New Wave possibly have flourished in an alternate postwar world dominated by Nazi occupation? Well… they couldn’t have. All this stuff isn’t in the game just because it looks and sounds cool. It creates an important storytelling dynamic that empowers the player to fight evil for a culture worth keeping. Machinegames have taken this approach throughout their run with the revived Wolfenstein games. BJ Blazcowicz’s battles against the Nazis have been violent and fantastical but the Nazis of the games, like the Nazis of the real world, are more than a threat to BJ’s life: they seek to eradicate the world he knows and loves. In New Order and New Colossus this existential struggle is set in the 1960s, shifting from the nightmare of a firmly established Nazi postwar order to the sparks of American political and cultural resistance. By 1980 Blazkowicz’s daughters Jess and Soph thumbs up and high five their way through some pretty enthusiastic killing of many, many Nazis, but not before grabbing Abby (their fellow progeny of another revolutionary legend, the totemically badass Grace), stealing an FBI helicopter and flying it to France somehow. There, the players will work their way through an open(ish) world divided in two: a hub located in the underground heart, figurative and literal, of the French Resistance and an overworld Paris dominated by long since victorious Nazis.

The underground safe haven is soaked in 1980s cultural tropes. CRT monitors abound, including those part of a hacked together grim parallel of the Macintosh II. Various parts of the underground resonate with the diagetic murmurs of 1980s new wave and electronica. Abby, now your tech wiz NPC ally, hangs out in retro nerd chic. In the game menus, players can go through reams of virtually recreated cassette tapes, floppy disks and home video boxes, all given an industrialised utilitarian aesthetic twist to reinforce the alternate in the history. Here the 1980s, the real 1980s in the mind of the player, survives There is an implicit claim here: despite the horrors of a sustained Nazi success, an uninterrupted control of a city associated with the freedoms of romance and art, something has survived against the odds. Something innately good, familiar. But none of it should be possible. Nothing about the Nazi plans for a world-encompassing Third Reich left room for synth-heavy pop music. Their vision of a perfect cultural order centred on Aryans in Lederhosen. The actual roots of New Wave came from a specific postwar context that trended hard towards the urban experience. The synth-heavy dreampop that would become associated in the public mind perhaps most of all with, of all the candidates, sleepy synth crooners A Flock Of Seagulls, owed its existence to punk. Musically, the form found its apotheosis in the homebrewed manic joy of The Ramones, sure; but punk was always about more than the music. Punk could be scraped together by people who wanted to express themselves but maybe hadn’t put the years in with an instrument. It was the antithesis of art school years before becoming art school’s purest form. As America moved from the somewhat decayed and exhausted decadence of the 1970s to a different kind of decadence altogether in the 1980s, punk birthed something new. And none of this could have happened under Nazi rule, where resistance of all types was unacceptable and social stability demanded cultural continuity. Punk wanted to break things down, punk was a reaction.

New Wave was a reaction too, ostensibly everything punk was not, as studded leather and sneers gave way to baggy shirts and insouciance. The hairstyles remained self-conscious but the hard tonal sounds of major chords faded as the harmonies took control, and guitar became part of an ensemble where keyboards held sway. It was a major shift, a reaction against punk and towards the overreach of glam rock and other examples of 1970s effervescence that the punk ethos had rejected. If all of this was a continuum, as perhaps it was - Lester Bangs, “America’s greatest rock critic”, insisted punk had existed for at least as long as there had been anything called rock ’n’ roll, it just finally took on a name of its own - then it reinforced, if nothing else, a continued investment by the free world, a phrase with meaning for many during the Cold War, in the profundities and depth of youth culture. With the thumbs up and high fiving and more than a few exclamations of “fuck!” thrown in, Jess and Soph celebrate their exuberance, their daring and their youth in defiance of their parents but with a clear moral goal: it’s so twentieth century. These characters are the children of their own greatest generation, delayed in their own timeline and weathered by an ongoing, sometimes futile rebellion rather than the glory of a successful re-invasion of Europe via amphibious landing. In Youngblood the relative serenity of the resistance’s underground base (the claustrophobia of its low ceilings never quite allowing anyone to relax) gives way to the open skies and police state when you go on missions. Here, the beauty of Paris remains, but interpolated, intersected, cut through by impositions of Nazi power. Watch towers and impossibly high and sheer walls bring physical divides to match the cultural ones.

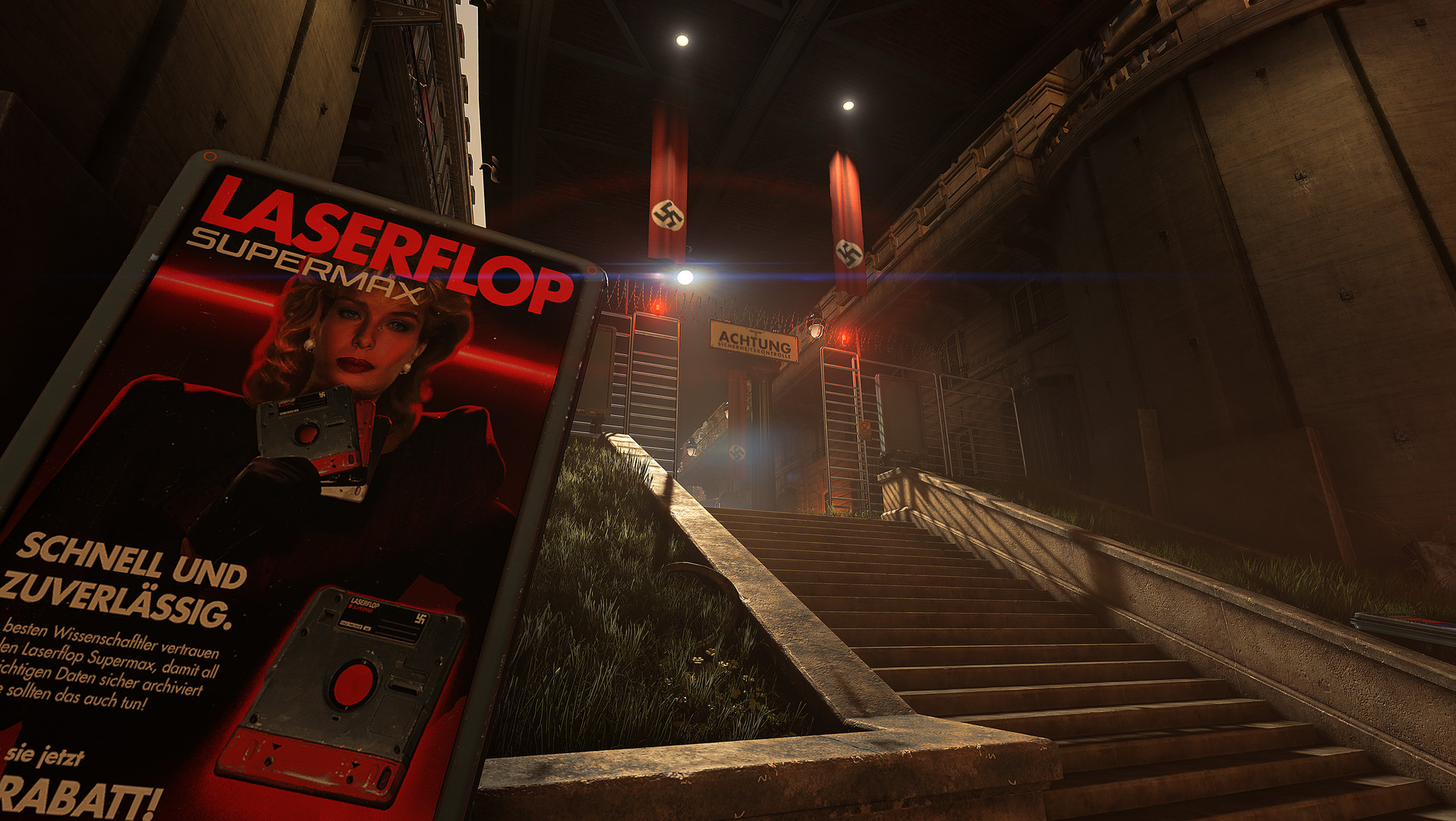

You run underneath the classic buildings, signage and balconies of Paris while evading the flamethrowers of Nazi supersoldiers. Above ground the totalitarian state rules all. Not just a historical totalitarian state either, but the one we have been visiting since The New Order, a postwar nightmare where Speer’s architectural visions became realised and the form of the Nazi state grew to fit ever more closely the function of continual, impenetrable oppression. The vibrancy of country’s identity, and of the 80s culture that we have a collective nostalgia for, has been pushed underground. In his 1962 novel The Man In The High Castle, Philip K. Dick wrote of characters effectively lost in the nightmare of an alternate reality and teased with the possibilities of the existence of our own. Dick’s work has clearly influenced Machinegames since The New Order. In Youngblood Jess and Soph embark on a journey of transcendence, rising up into occupied territory and coming home to the welcoming sounds of freedom. That freedom sounds like synthpop gives the player comforting reassurance the French Resistance has kept the spirit of a free postwar world alive. That perhaps, even given Machinegames’s implicit acceptance of the myriad imperfections of the postwar reality we have all inherited, the world and popular culture that rose from the ashes of the largest conflict in human history was, in a way, innately good. The Blazkowicz sisters are fighting to bring a tortured alternate history back to the correct timeline, albeit metaphorically. And the player wants them to succeed.